YWCA Greater Cincinnati had the opportunity during the 2017-2018 school year to work with the Joe Torre Safe at Home Foundation to implement a program called Margaret’s Place for the first time in Cincinnati, Ohio. Margaret’s Place is a dedicated safe room in schools where students who have been impacted by violence and trauma can go to talk or hang out in a comfortable environment that feels safe to them; A place where respect and confidentiality are the rule. The program falls in line with YWCA’s mission in becoming a trauma informed agency as the program serves students 7th-9th grade by providing them with free preventative and intervention services.

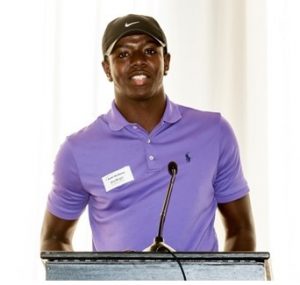

A key piece of Margaret’s Place is Peer Leadership. Peer Leaders are youth ambassadors for Margaret’s Place and are trained in public speaking, conflict mediation, violence and abuse prevention and play an active role in educating their peers. Giovanni Wright (pictured left) was a senior at Riverview East Academy when he became a peer leader. Gio grew up in a single household in OTR as the second oldest of 8 siblings. Gio states that he took on a lot of responsibility at an early age and felt like he had to raise his younger siblings and protect them so his mother could work and support his family. Gio’s father was away in Jail. Gio reports that he dealt with homelessness and abuse in his household. Because of the many experiences Gio had, he wanted to help others at his school who experience similar traumas. He felt that by being a peer leader he could do just that. Gio felt alone for the majority of his life and wanted to work towards making others feel that they aren’t alone by sharing his story. Gio wanted to make sure his peers had someone trusting to lean on and he became that support. Gio truly made a huge impact on his peers during his last year at Riverview and was able to travel to New York City to share his story alongside Joe Torre at the annual Safe at Home Golf Outing.

Gio graduated from high school and will begin his studies in Social Work/ Psychology at UC this fall. He plans to continue to build on his strength- helping people.